For most of the 20th century, Honduras was relatively free of the political violence that plagued its Central American neighbors: Guatemala, Nicaragua and El Salvador. But in the 1970s and 1980s, Honduras became the staging ground for the U.S.-backed covert war against Latin American communism. A U.S. trained military intelligence unit—the notorious Battalion 316—carried out a campaign of torture, extrajudicial killing, and state-sponsored terror against Honduran civilians.

From Backwater to Frontline in the Cold War: 1821-1981

Honduras—once home to ancient Mayan civilization—was colonized by the Spanish in the 16th century. Following independence in 1821, Honduras settled into characteristic patterns of dictatorial politics and plantation economics. By the late 19th century, Honduras had devolved into the quintessential “banana republic.” American corporations like the United Fruit Company dominated its economic and political life. This status quo continued in relative peace until regional conflict crept across Honduras’ borders. [1]

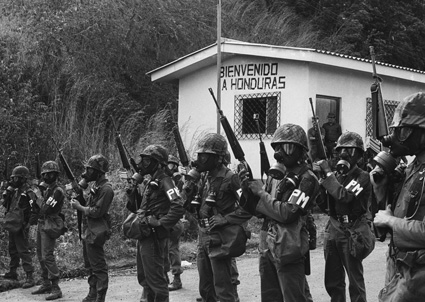

With the communist Sandinista government entrenched in Nicaragua and the outbreak of the Salvadoran civil war in 1981, Honduras would be transformed into a staging ground for covert operations. The U.S. poured military aid and advisors into the Honduran army and set up base camps for the Contras—a right-wing paramilitary force cultivated by the U.S. to overthrow the Sandinistas in Nicaragua.

Central to this transformation was Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces, General Gustavo Álvarez Martínez, who had graduated from U.S. Army School of the Americas. A zealous anti-communist, Álvarez endorsed the ‘Argentine approach’ to managing the country’s left wing. Under his tenure, Honduras became an active front in the Contra war, and many Hondurans who dissented disappeared into secret prisons, their families left to wonder at their fate. [2]

Battalion 316: Honduran Death Squad

The worst began in August 1980, when 25 Honduran army officers landed at an airstrip in a southwestern desert of the United States. There, they spent six months being trained in the latest surveillance and interrogation methods by CIA and FBI instructors. [3]

The courses continued in Honduras. According to declassified documents, the United States provided funds for Argentine counterinsurgency experts to train anti-communist forces in Honduras in 1981. Torturers from the infamous Argentine military intelligence Battalion 601—veterans of Argentina’s “Dirty War” and Operation Condor—worked side by side with CIA instructors at training camps where lessons were demonstrated on live prisoners. [4]

The pupils studied a curriculum that married psychological techniques and physical tortures, including electro-shock, freezing temperatures, and suffocation. The program’s graduating class would form the core of Honduras’s most notorious death squad: Battalion 316.

According to declassified CIA documents, Battalion 316 was formed by General Álvarez Martínez, and placed under the direct control of Lt. Col. Juan Lopez Grijalba, of the Armed Forces General Staff. [3] The battalion was headquartered in the capital city, Tegucigalpa, in what used to be the Morazán Athletic Club. Within the battalion, certain units would be in charge of torturing prisoners in the holdings cells of the headquarters, or in secret safe houses outside the capital. Other units were charged with abductions; still others were responsible for executions and disposal of bodies.

Battalion 316’s modus operandi was to abduct their victims in unmarked vehicles. The prisoners would then be interrogated and tortured. Many were summarily executed, their bodies dumped in unmarked graves. From the late 1970s until 1988, an estimated 184 persons were disappeared or extra-judicially killed; many more were abducted and tortured. [3]

In 1981, the U. S. State Department acknowledged the role of the Honduran military in these human rights abuses. Specifically, the State Department stated that the “minions” of General Alvarez Martinez were carrying out “officially-sponsored/sanctioned assassinations of political … targets.” [5]

Although the State Department internally recognized the scope of human rights abuses in Honduras, the version presented by the Reagan administration to Congress and to the American public was that of denial. In 1982, then U.S. ambassador to Honduras John Negroponte wrote in The Economist: “It is simply untrue to state that death squads have made their appearance in Honduras.” [6]

Uncovering the Disappeared: Transitional Justice in Honduras

Starting in the mid-1980s, the civilian government of Honduras struggled to demilitarize the police force and the political sphere in general. In the same period, efforts were made to document evidence of human rights abuses committed in the 1970s and 1980s.

Much of what we know about Battalion 316’s operations emerged from a 1986 case brought before the Inter-American Court of Human Rights (IACtHR). In the case of Velásquez Rodríguez v. Honduras, the IACtHR found Honduras responsible for the forced disappearances that claimed the lives of Saúl Godínez Crúz and Angel Manfredo Velásquez Rodríguez. The case was based on a 1981 complaint brought before the Inter-American Commission of Human Rights by the victims’ families in an effort to learn their whereabouts. » Read here for the text of the resolutions passed by the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights.

In 1993, the testimony of former Battalion 316 agents before the IACtHR, and case studies of 180 reported disappearances, were published in The Preliminary Report of the National Commissioner for the Protection of Human Rights in Honduras: “Honduras, The Facts Speak for Themselves.” Beginning in 1994, the government of President Carlos Reina made a concerted effort to curtail the autonomy of the military and to develop mechanisms of accountability for the armed forces. The next year, the legislature passed a constitutional amendment which placed the security forces under civilian control.

Revelations in the United States: the CIA’s Role in Torture

In 1995, the Baltimore Sun ran a four-part series based on interviews with Florencio Caballero, a former member of Battalion 316, and with torture survivors from Honduras. [7] Through these interviews, a portrait began to emerge of the CIA’s role in the operations of Battalion 316.

Read more…

The Struggle for Accountability in Honduras

Another important component of the movement for transitional justice in Honduras has been the effort to prosecute human rights abusers in national and international courts.

On July 25, 1995, the Honduran government launched its first criminal prosecution of a military officer for human rights abuses. Two active-duty and eight retired army officers were charged with attempted murder and illegal detention in connection with the disappearance and torture of six university students in 1982. The defendants claimed that they were immunized under the 1987 and 1991 amnesty laws and refused to appear in court.

In 1998, one officer, Col. Juan Blas Salazar Mesa, was found guilty of the charges, but the court ruled that the amnesty laws prevented him from being punished. The case was appealed to the Supreme Court, where the amnesty laws were eventually deemed unconstitutional in 2000. In February 2000, the Honduran government announced that it would begin to pay $2.1 million in reparations to the families of 19 of the 184 acknowledged victims murdered by the 316 Battalion. [8]

In 2003, Salazar Mesa was convicted of illegal detention and sentenced to four years in jail. That same year, the court issued arrest warrants for two retired colonels, Juan Evangelista López Grijalba—who is the subject of CJA’s U.S. civil suit, Reyes v. Grijalba—and Julio César Funez Alvarez, in connection to the six students case. Later in 2003, retired Gen. José Amílcar Zelaya Rodríguez, the owner of the country cottage where the six students had been sequestered and tortured, was arrested on charges of complicity. [8]

In a speech before human rights NGOs on November 4, 2004, President Maduro accepted responsibility on behalf of the Honduran government for human rights abuses in the 1980s and promised to comply with Inter-American Court of Human Rights (IACHR) rulings. [9] However, impunity for human rights abuses continues to be a reality of the Honduran legal system.

On January 26, 2004, the charges against Col. López Grijalba for illegal detention were dismissed. The Public Ministry appealed the decision, but on September 28, 2007, the Supreme Court upheld the dismissal of the human rights charges. While other disappearance cases continue to work through the courts, progress in prosecuting individual offenders has been slow going.

In December 2007, CJA completed its first human rights training program: “Prosecuting Human Rights Crimes in National Courts.” The training brought together 80 Honduran prosecutors with a faculty of legal practitioners from Latin America, Spain and the United States with experience and expertise in the prosecution of human rights abusers.

The problem of impunity is compounded by the fact that severe human rights abuses continue to occur with alarming regularity. In recent years, security forces have been implicated in cases of torture and extrajudicial killing targeting environmental activists, human rights lawyers and advocates from the GLBTQ community. For more information, see Amnesty International’s 2008 human rights report on Honduras.

In March 2008, the UN Working Group on Enforced or Involuntary Disappearances reported that 125 cases of disappearance from the early 1980s were still pending clarification. [10]

2009 Coup D’État

Just when it seemed that Honduras was poised to confront its human rights legacy, President Manuel Zelaya was removed from power at gunpoint and forced into exile by the Honduran army, acting on the orders of the Supreme Court and Congress. Zelaya, a populist-reformist politician, had ordered a referendum on extending the constitutional term limit of the presidency, a move that drew the ire of opposition and centrist politicians alike.

Despite claims that the coup was a justified attempt to protect the constitution from a presidential power-grab, the new de facto government’s claims to legitimacy have been undermined by the presence of notorious human rights abusers at the heart of the new administration. Most alarmingly, Billy Joya, the former leader of Battalion 316, has become a prominent spokesman for the de facto regime. The families of the victims of Battalion 316 and local and international human rights groups have raised serious concerns that the ouster of President Zelaya will spell a new era of impunity for human rights crimes in Honduras. [11]

Notes

[1] Honduras: A Country Study, Ed. by Tim Merrill, Federal Research Division, U.S. Library of Congress, December 1993. Available at: http://memory.loc.gov/frd/cs/hntoc.html Accessed: August 17, 2009.

[2] Cold War Pawn: Honduras in the 1980s. May I Speak Freely?, Available at: http://www.mayispeakfreely.org/index.php?gSec=doc&doc_id=32 Accessed: August 17, 2009.

[3] The Facts Speak for Themselves: The Preliminary Report on Disappearances of the National Commissioner for the Protection of Human Rights in Honduras, translation by Human Rights Watch/Americas and the Center for Justice and I nternational Law (CEJIL), July 1994. Available at: http://www.hrw.org/en/reports/1994/07/01/facts-speak-themselves Accessed August 17, 2009.

[4] Prisoner Abuse: Patterns from the Past, National Security Archive Electronic Briefing Book No. 122, May 2004. Available at: http://www.gwu.edu/~nsarchiv/NSAEBB/NSAEBB122/ Accessed: August 17, 2009.

[5] U.S. Embassy Tegucigalpa cable 4314 (NODIS), “Reports of GOH Repression and Approach to Problem,” June 17, 1981.

[6] Testifying to Torture, New York Times, July 17, 1988. Avaiable at: http://www.nytimes.com/1988/07/17/magazine/l-testifying-to-torture-332588.html Accessed: August 17, 2009

[7] “When a wave of torture and murder staggered a small U.S. ally, truth was a casualty”. Cohn, Gary; Ginger Thompson. Baltimore Sun. June 11, 1995. Available at: http://www.baltimoresun.com/news/maryland/bal-negroponte1a,0,294534.story Accessed: August 17, 2009. (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/5j6KNYW6F)

[8] “The Quest for Justice: Efforts to Prosecute Honduran Human Rights Abusers”, May I Speak Freely?, Available at: http://www.mayispeakfreely.org/index.php?gSec=doc&doc_id=35 Accessed: August 17, 2009.

[9] Honduras: 2004 Country Reports on Human Rights Practices, Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor, U.S. State Department, February 28, 2005. Available at: http://www.state.gov/g/drl/rls/hrrpt/2004/41765.htm Accessed: August 17, 2009.

[10] UN Human Rights Council, Report of the Working Group on Enforced or Involuntary Disappearances,

25 February 2009, 38 at 169. A/HRC/10/9, available at:

http://www.unhcr.org/refworld/docid/49c778772.html Accessed: August 17,

2009.

[11] A Cold War Ghost Reappears in Honduras, Ginger Thompson, New York Times, August 7, 2009. http://www.nytimes.com/2009/08/08/world/americas/08joya.html Accessed: August 17, 2009.