CASE STATUS

Active

HUMAN RIGHTS ISSUES

COUNTRY

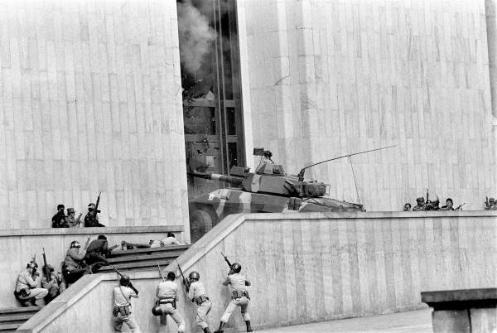

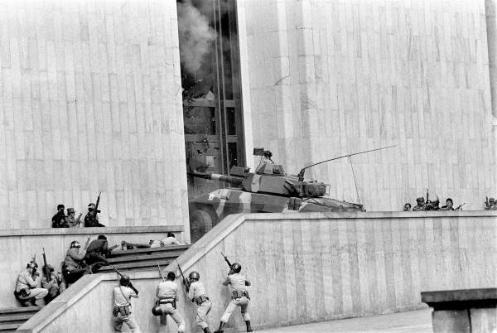

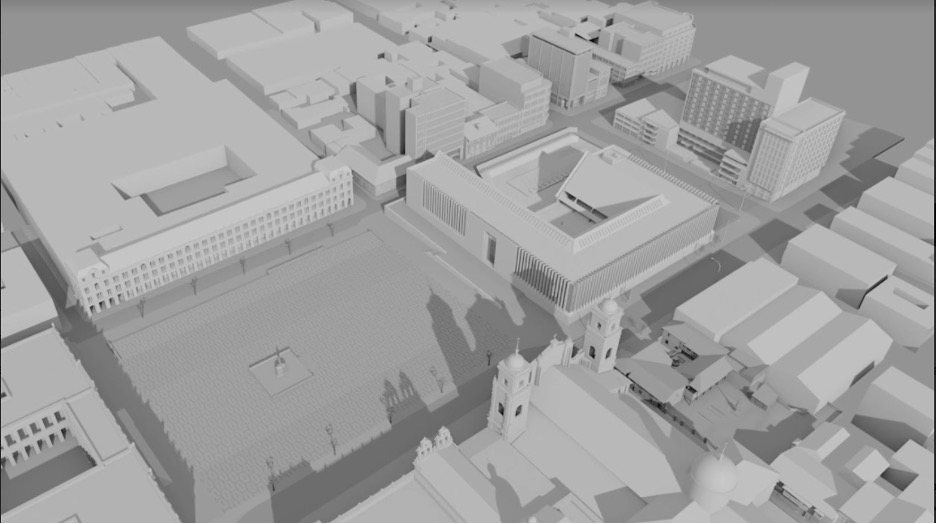

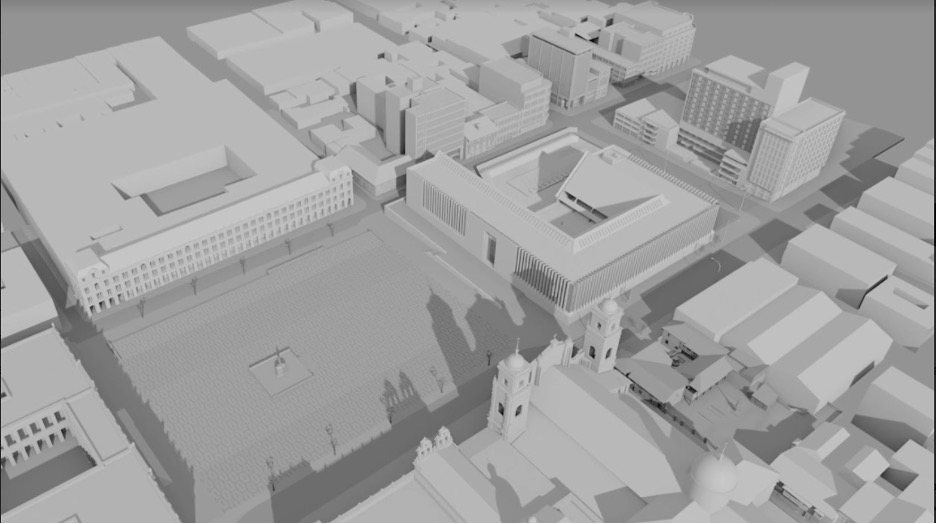

On the morning of November 6, 1985, approximately 35 members of the M-19 guerrilla group launched an armed attack on Colombia’s Palace of Justice in Bogotá—the seat of Colombia’s Supreme Court and Judicial Council, the two highest courts in the country. Civilians in the building were trapped and held hostage. The Colombian military reacted quickly and forcefully, deploying its 13th Brigade, based in Bogotá, and other forces. Over the next two days, the Colombian military engaged in a dramatic operation to retake the Palace of Justice and release the hostages, with brutal results that were at first understood as legitimate and even necessary. The siege on the Palace of Justice—which remains among the most iconic events in modern Colombian history—left the building largely destroyed and resulted in the disappearances of over a dozen civilians and the deaths of nearly one hundred civilians, including eleven Supreme Court justices.

Throughout the rescue operations, the hostages were escorted out of the Palace of Justice by the military. For many, this was the end of the two-day nightmare at the Palace: after a brief questioning, most of the rescued civilians were permitted to leave. However, some of these rescued hostages were deemed “special”: suspected of being guerillas or sympathizers, they were labeled “especiales” and were interrogated, tortured, and in most cases, extrajudicially killed or forcibly disappeared. The especiales system, as it came to be known, was a part of the Colombian military’s brutal and no-holds-barred “war” against guerilla terrorism.

In the aftermath of the siege, the military undertook a brazen and systematic operation to cover up their crimes. In the case of some victims, the military returned the bodies to the Palace of Justice and attributed their deaths to the guerillas or crossfire from the military’s retaking of the Palace. Some bodies simply disappeared. Those tortured and released were threatened to keep quiet. The military unrelentingly maintained that the high civilian death toll was the result of individuals being killed during the siege and that missing remains were due to the fire that engulfed much of the Palace of Justice on the evening of November 6, 1985.

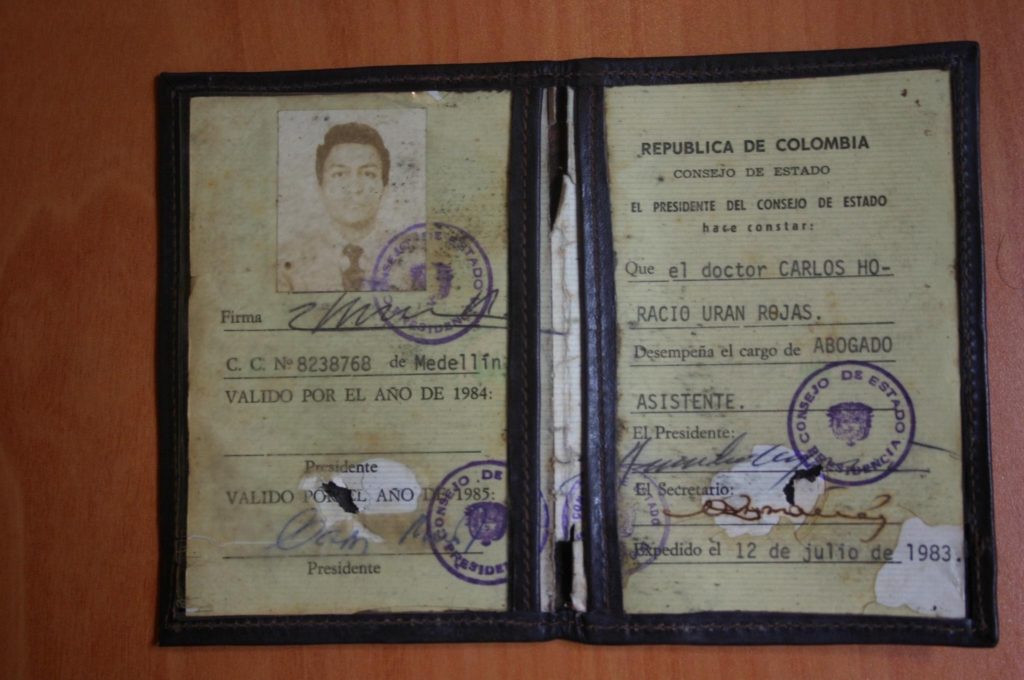

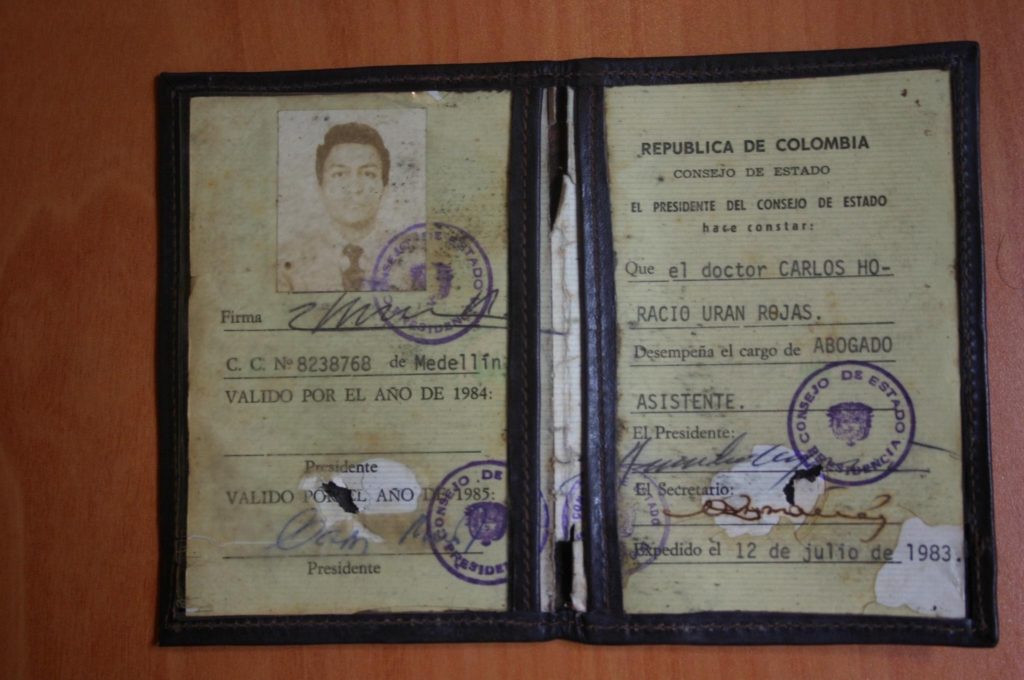

One victim of the military’s especiales system was Magistrate Carlos Horacio Urán Rojas, an Auxiliary Justice of the Council of State. His body was found inside the Palace of Justice, stripped naked and washed, with a close-range gunshot wound in the temple. For decades after his death, Magistrate Urán’s wife and four young daughters believed the story the military told them: that their husband and father had been killed in the crossfire during the retaking of the Palace of Justice, an unfortunate victim of circumstance.

In the intervening decades, however, the military’s narrative began to unravel. Witness testimony, video and documentary evidence, and military radio communications emerged, revealing that many individuals who were later found dead or whose remains were never recovered were escorted out from the Palace of Justice in the custody of the military. In 2007, during a court-ordered search, Magistrate Urán’s belongings were discovered hidden in a locked vault inside the 13th Brigade compound. That same year, video evidence and eyewitness testimony surfaced, all establishing that Magistrate Urán had exited the Palace of Justice in the custody of the military, injured but very much alive. The truth became clear to the Urán family: hours after news cameras filmed him exiting the Palace of Justice alive, flanked by military officers, Magistrate Urán’s body was returned to the building, bearing marks of torture and a gunshot wound to the head.

Despite the Urán family’s tireless efforts since then, no individual has ever been held legally responsible for Magistrate Urán’s torture and extrajudicial killing. The Colombian government’s criminal investigation into Magistrate Urán’s death has stalled since 2007. In 2014, a landmark decision by the Inter-American Court of Human Rights found the State of Colombia responsible for torture, enforced disappearances, and extrajudicial killings committed as part of the military’s retaking of the Palace of Justice, including the extrajudicial killing of Magistrate Urán. Despite this judgment, Colombia has still taken no action to hold those responsible to account.

On February 15, 2022, three of Magistrate Urán’s daughters, after decades of seeking justice in Colombia, filed a case against Lieutenant Colonel Luis Alfonso Plazas Vega for his role in their father’s torture and extrajudicial killing. Plazas Vega led the military units charged with retaking the Palace of Justice and was allegedly actively involved in the military’s unlawful system to identify, interrogate, torture and kill or forcibly disappear rescued hostages, which included Magistrate Urán. The case was filed in the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of Florida under the Torture Victim Protection Act. Magistrate Urán’s three daughters are represented by CJA and its co-counsel Wilson, Sonsini, Goodrich & Rosati. Read the complaint.

On May 12, 2022, Plazas Vega moved to dismiss plaintiffs’ suit on procedural grounds – arguing that plaintiffs had failed to exhaust local remedies and that the court should abstain from addressing the suit. On March 14, 2023, the court denied the motion to dismiss and allowed the case to proceed. Read the order.

On November 16, 2023, plaintiffs and Plazas Vega filed cross-motions for summary judgment on Plazas Vega’s exhaustion of local remedies affirmative defense. Plaintiffs argued that Plazas Vega did not meet his burden to show that they had failed to exhaust any alleged local remedies and that, in any event, they had exhausted all adequate and available local remedies in Colombia. On June 18, 2024, following oral arguments, the Court ruled that Plazas Vega had failed to carry his burden on the issue of exhaustion of local remedies and granted plaintiffs’ motion in full, allowing the case to proceed.

La Toma del Palacio de Justicia

En la mañana del 6 de noviembre de 1985, aproximadamente 35 miembros del grupo guerrillero M-19 lanzaron un ataque armado contra el Palacio de Justicia de Colombia en Bogotá — la sede de la Corte Suprema y el Consejo de Estado de Colombia, los tribunales dos más altos del país. Los civiles en el edificio estuvieron atrapados y los mantuvieron como rehenes. El ejército colombiano reaccionó rápida y contundentemente, desplegando su Décima Tercera Brigada, con sede en Bogotá, y otras fuerzas. Durante los siguientes dos días, el ejército colombiano mantuvo una operación dramática para recuperar el Palacio de Justicia y liberar a los rehenes, con resultados brutales que en un principio se entendieron como legítimos e incluso necesarios. La toma del Palacio de Justicia — que sigue siendo uno de los eventos más emblemáticos de la historia moderna de Colombia — dejó el edificio destruido en gran parte y resultó en la desaparición de más de una docena de civiles y la muerte de casi cien civiles, incluidos once magistrados de la Corte Suprema.

Durante las operaciones de rescate, efectivos de las fuerzas de seguridad escoltaron a los rehenes fuera del Palacio de Justicia. Para muchos, este fue el final de la pesadilla de dos días en el Palacio: después de un breve interrogatorio, a la mayoría de los civiles rescatados se les permitió irse. Sin embargo, algunos de estos rehenes rescatados fueron considerados “especiales”: considerados sospechosos de ser guerrilleros o simpatizantes, fueron tachados como “especiales” y fueron interrogados, torturados y, en la mayoría de los casos, asesinados extrajudicialmente o sometidos a desaparición forzada. El sistema de “especiales”, como llegó a ser conocido, era parte de la guerra brutal y sin cuartel del ejército colombiano contra el terrorismo guerrillero.

Tras las operaciones para acabar con la toma del Palacio de Justicia, las fuerzas de seguridad emprendieron una operación descarada y sistemática para ocultar sus crímenes. En el caso de algunas víctimas, las fuerzas de seguridad devolvieron los cuerpos al Palacio de Justicia y atribuyeron sus muertes a las guerrillas o al fuego cruzado de la retoma militar del Palacio. Algunos cuerpos simplemente desaparecieron. Los torturados y liberados fueron amenazados para que callaran. Las fuerzas militares sostuvieron incansablemente que el alto número de civiles muertos era resultado a las muertes de personas durante el asedio y que los restos que no hallaron se debieron al incendio que consumió gran parte del Palacio de Justicia la noche del 6 de noviembre de 1985.

Una de las víctimas del sistema militar de especiales fue el magistrado Carlos Horacio Urán Rojas, Magistrado del Consejo de Estado. Su cuerpo fue encontrado dentro del Palacio de Justicia, desnudo y lavado, con una herida de bala a corta distancia en la sien. Durante décadas después de su muerte, la esposa del magistrado Urán y sus cuatro hijas creyeron la historia que les contaron los militares: que el magistrado Urán había muerto en el fuego cruzado durante la recuperación del Palacio de Justicia, una víctima lamentable de las circunstancias.

Sin embargo, en las décadas siguientes, la narrativa de los militares comenzó a desmoronarse. Surgieron testimonios de testigos, evidencia en vídeos y documentos, y comunicaciones militares por radio, que revelaron que muchas personas que luego fueron encontradas muertas o cuyos restos nunca fueron recuperados fueron escoltadas fuera del Palacio de Justicia bajo la custodia de las fuerzas armadas. En 2007, durante un allanamiento ordenado por un tribunal, las pertenencias del magistrado Urán fueron descubiertas escondidas bajo llave dentro del recinto de la Décima Tercera Brigada. Ese mismo año, surgieron pruebas en video y testigos presenciales, todo los que estableció que el magistrado Urán había salido del Palacio de Justicia bajo la custodia de los militares, herido pero muy vivo. La verdad quedó clara para la familia Urán: horas después de que las cámaras de los noticieros lo filmaran saliendo con vida del Palacio de Justicia, flanqueado por militares, el cuerpo del magistrado Urán fue devuelto al edificio con marcas de tortura y una herida de bala en la cabeza.

A pesar de los esfuerzos incesantes de la familia Urán desde entonces, nunca se ha responsabilizado jurídicamente a ninguna persona por la tortura y asesinato extrajudicial del magistrado Urán. La investigación penal del gobierno colombiano sobre la muerte del magistrado Urán está estancada desde 2007. En 2014, una decisión histórica de la Corte Interamericana de Derechos Humanos halló al Estado de Colombia responsable de las torturas, desapariciones forzadas y asesinatos extrajudiciales cometidas como parte de la retoma militar del Palacio de Justicia, incluido el asesinato extrajudicial del magistrado Urán. A pesar de esta decisión de la corte, Colombia aún no ha tomado ninguna medida para hacer rendir cuentas a los responsables. Tres de las hijas del magistrado Urán, después de décadas de buscar justicia en Colombia, ahora han presentado este litigio civil, representadas por CJA, conjuntamente con el bufete de abogados Wilson, Sonsini, Goodrich & Rosati, buscando justicia por el asesinato de su padre.

El 15 de febrero de 2022, tres de las hijas del magistrado Urán, tras décadas de búsqueda de justicia en Colombia, presentaron una demanda contra el teniente coronel Luis Alfonso Plazas Vega por su papel en la tortura y la ejecución extrajudicial de su padre. Plazas Vega dirigió las unidades militares encargadas de la retoma del Palacio de Justicia y supuestamente participó activamente en el sistema ilegal de los militares para identificar, interrogar, torturar y matar o desaparecer por la fuerza a los rehenes rescatados, entre los que se encontraba el magistrado Urán. El caso se presentó en el Tribunal de Distrito de Estados Unidos para el Distrito Sur de Florida en virtud de la Ley de Protección de las Víctimas de la Tortura. Las tres hijas del Magistrado Urán están representadas por CJA y sus co-abogados del bufete Wilson, Sonsini, Goodrich & Rosati. Lea la demanda.

El 12 de mayo de 2022, Plazas Vega peticionó para desestimar la demanda por razones de procedimiento, argumentando que los demandantes no habían agotado los recursos locales y que el tribunal debería absternerse. El 14 de marzo de 2023, el tribunal denegó la petición para desestimar y permitió que la causa procediera. Lee la orden.

El 16 de noviembre de 2023, los demandantes y Plazas Vega presentaron peticiones cruzadas de juicio sumario sobre la defensa afirmativa de agotamiento de recursos locales de Plazas Vega. Los demandantes argumentaron que Plazas Vega no cumplió con su carga de demostrar que no habían agotado los recursos locales alegados y que, en todo caso, habían agotado todos los recursos locales adecuados y disponibles en Colombia. El 18 de junio de 2024, después de los argumentos orales, la Corte dictaminó que Plazas Vega no había cumplido con su carga en el tema del agotamiento de los recursos locales y concedió la moción de los demandantes en su totalidad, permitiendo que el caso procediera.